Developing a Linear Regression Algorithm

The Linear Regression is specified as;

where $X_0 = 1$

and;

$(\theta_0, \theta_1, \theta_2,…, \theta_n)$ are the optimized thetas,

$(X_1, X_2,…, X_n)$ are the features or independent variables.

where our algorithm learns from our training data and outputs a prediction hypothesis $h_{(\theta)}(X)$ function which is used to predict actual values of $Y$.

where $\epsilon$ is the Error term.

There are two ways to compute these optimized parameters;

- Gradient Descent

- Normal Equation

A general overview of the process;

- Import required libraries

- Develop model using both Gradient Descent and Normal Equation

- Test Model using both methods on a dataset and compare with Sklearn out-of-the box model using the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE)

Let’s import the important libraries:

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

from sklearn import datasets

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error

1. Gradient Descent

m = Number of Samples

def cost_function(X, y, init0s): #Returns the cost value given the theta values.

m = len(X) #m is the length of X i.e the number of samples

cost = 1/(2*m)*np.sum((np.dot(init0s, np.transpose(X)) - y)**2)

return cost

def partial_derivs(X, y, init0s): #Returns a list of updated thetas

m = len(X)

predicted = (np.transpose(init0s) * X).sum(axis = 1)

diff = (predicted - y)

diff_transpose = np.transpose(diff[:,np.newaxis])

#Add a new axis to make it vectorizable for dot product

updated0s = init0s - alpha*((1/m))* np.dot(diff_transpose, X)[0,:]

#Remove the extra dimension/axis

return updated0s

def gradient_descent(X, y,init0s):

#Returns the optimal theta value and a list of costs for each iteration

costs = [cost_function(X, y,init0s)]

for i in range(epochs):

init0s = partial_derivs(X, y,init0s)

c = cost_function(X, y, init0s)

costs.append(c)

return init0s, costs

def predict(X_test, y_test, optimal0s):

predicted = (np.transpose(optimal0s) * X_test).sum(axis = 1)

rmse = mean_squared_error(y_test, predicted)

return predicted, rmse

Let’s test out our Linear Regression model on a dataset

data = datasets.make_regression(100,2, noise = 1) #100 samples with two features

print(data)

(array([[ 0.0465673 , 0.80186103],

[-2.02220122, 0.31563495],

[-0.38405435, -0.3224172 ],

[-1.31228341, 0.35054598],

[-0.88762896, -0.19183555],

[-1.61577235, -0.03869551],

[-2.43483776, -0.31011677],

[ 2.10025514, 0.19091548],

[-0.50446586, -1.44411381],

...

[-2.06014071, 1.46210794],

[-0.63699565, 0.05080775],

[ 1.25286816, -0.75439794],

[ 1.04444209, 0.81095167],

[ 1.23616403, -1.85798186],

[ 2.18697965, 1.0388246 ],

[-0.07557171, 0.48851815],

[ 0.59357852, 0.40349164]]), array([ 72.36523412, -37.14156866, -41.38412368, -12.64791154,

-43.66708325, -55.37682786, -104.14429178, 86.72486169,

-141.78457722, -57.09382215, 21.11295519, 37.8001059 ,

199.5500905 , 25.81364514, 209.42911479, 128.20604958,

-26.3460515 , -88.2946975 , 45.84342752, -29.55352689,

...

102.81595456, -28.66364244, 100.21268739, -73.03008828,

113.01648102, 109.17545836, -31.30447011, 36.51499677,

-88.82089559, -3.4467088 , 53.45209032, -87.40808263,

-99.40016109, 5.04506704, 56.12030581, 84.54855562,

59.02884225, -17.38215753, -24.1274554 , 102.33610869,

-120.59599797, 160.11974736, 39.67236875, 55.97220222]))

We need to carry out some preprocessing on data.

- Add the $X_0$ column with 1’s

- Split the data into Train and Split for Validation

def preprocess_data(data):

X = data[0]

y = data[1]

#copy = data.copy

ones = np.ones(len(X))

X = np.c_[ones, X]

return train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.33, random_state=1)

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = preprocess_data(data)

#y_train

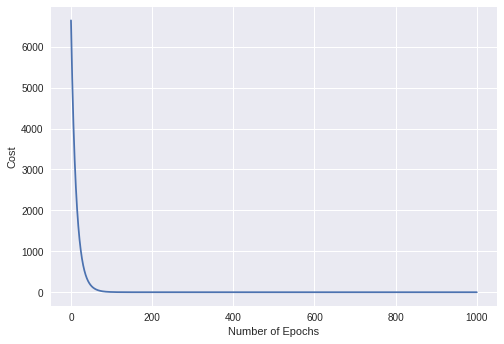

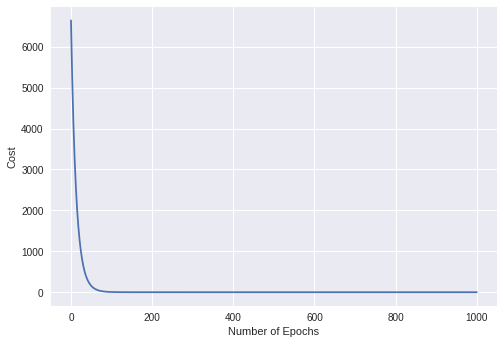

Plot the Cost values

epochs = 1000 #Number of Iterations

alpha = 0.04

init0s = np.zeros(3)

y = gradient_descent(X_train, y_train, init0s)[1]

x = np.arange(len(y))

plt.xlabel("Number of Epochs")

plt.ylabel("Cost")

plt.plot(x,y)

[<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x7f2d50903ac8>]

Optimal Theta Values

gradient_descent(X_train, y_train, init0s)[0]

array([ 0.19357013, 32.19125678, 86.08455637])

So our multivariable linear regression prediction model is;

$h_{(\theta)}(X)$ = 0.19357013$X_0$ + 32.19125678$X_1$ + 86.08455637$X_2$

Compare our model’s RMSE with Sklearn’s

epochs = 1000 #Number of Iterations

alpha = 0.04

init0s = np.zeros(3)

predict(X_test, y_test, gradient_descent(X_train, y_train, init0s)[0])[1]

#Returns the model RMSE

1.4033255546659869

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

lr = LinearRegression()

lr.fit(X_train, y_train)

prediction = lr.predict(X_test)

rmse = mean_squared_error(y_test, prediction)

rmse

1.4033255545376973

Our model’s RMSE value (1.40332) is comparable to Sklearn’s RMSE value (1.40332)

2. Normal Equation

where $\theta_j = (X^TX)^{-1}X^TY$

def normal_equation(X, y):

xtrans = np.transpose(X)

inv = np.linalg.pinv(np.dot(xtrans, X))

#use pinv for nonivertible singular matrices and use inv for normal invertible matrices

optimal0s = np.dot(np.dot(inv, xtrans), y)

return optimal0s

normal_equation(X_train, y_train)

array([ 0.19357013, 32.19125678, 86.08455637])